|

| Ai Weiwei the Great |

The sun, which had not made an appearance since I stepped onto China’s soil over a week ago, wiped away polluted, persistent gray heavens on Sept. 15th. The Beijing air was breathable and the brick walls and bicycles and tedious traffic seemed to be refreshed. Thanks to the help of many art friends, it was time to meet with probably the most controversial artist in the world today, at his home-studio where he has been on house arrest because he tells it like it is about life in China. He is a man who pursues freedom, freedom of expression, of life, of liberty and of movement. You either love him or hate him, I guess. I loved him with an exclamation point!

Ai Weiwei is one of the kindest, gentlest, and most unabashed advocates I’ve ever met.There is not a medium in the arts he has not tackled, from being architect on the extraordinary Bird’s Nest for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, to turning millions of sunflower seeds into ceramic pieces. The government considers him a revolutionary. To me, that’s not such a bad thing to be, since in my faith, Jesus walked that road and told those of us who are his servants, we had to do that too. He too has been beaten, imprisoned, degraded, charged falsely. The China government’s weapon against him has been censorship, and that affects more than him. Many think he has amassed millions and isolated himself by being the enigma to the modern Chinese leaders. Yet, Ai Weiwei just wants to create art, point out inconsistencies and abuses of fairness and respect, and to be free to travel and spend time with his one child, a son. Ai Weiwei has a staff of 40 who have assisted him through thick or thin, with or without pay, and they make sure what he aims to create gets created.

|

| Weiwei’s new logo |

The world knows about Ai Weiwei. The government treats him as a criminal. Censorship is not only against him, but all who reside or visit this huge nation: Google, Facebook, U-Tube, Blogger, and many other life lines to each other in the digital age have been blocked, no matter who is concerned. His crime is speaking up and criticizing the unfair. When there was an earthquake in Sechuan, and so many children were killed, and coverups and corruption interfered with recovery, Ai WeiWei exposed the “tofu-dreg schools” which collapsed so easily and took the lives of so many youngsters. He is still about getting names of those who died to the forefront, so that the masses are not treated like the masses but as if they were individuals who had lived on this earth. He has uncovered more than 5400 names of dead children and honors them by remembering their birthdays on Twitter. He was arrested and beaten because of his involvement in this and was left with a cerebral hemorrhage. He still fights headaches.

After the Cultural Revolution ended, when the gates opened and artists leaped into the arena with an energy not seen anywhere, Ai Weiwei was a part of the early avant guard art group called “Stars” – which included many who also became controversial artists: Ma Desheng, Wang Keping, Huang Rui, Li Shuang, Zhong Acheng and Qu Leilei. Many of these live outside their native country. Ai Weiwei, also, had lived in New York 1981-1993 where he was exposed to Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, artists who also broke the traditional to force the public to look at art and its meaning in a different way. But his call was to use art to stir up freedom in his homeland.

|

| Entrance to Weiwei’s |

We reached Ai WeiWei’s brick walled compound, which he built in the Cao Chang Di District, a part of Beijing’s remote area converted into an innovative art community. Other artists followed him there. Our visit day was such a brilliant morning and the early, unclouded sun felt good on my shoulders, I knew this was a good omen. Outside the walls and the simple metal door that enters his home and studio, a bicycle with a bouquet of flowers in its basket, leans against a lamppost, waiting there day in and day out, indicative that he wants to ride away into freedom. The flowers are fresh each day, as is his hope. Bicycles, which he turns into architectural structures at times, filling enormous warehouse space as he connects them in strange ways, are a frequent source of his installations and sculptures, as are doors and other symbols of confinement or freedom. Doors of palaces kept out the peasants, the workers, kept out information and knowledge, kept in the unknown power that invoked fear. But when I crossed the threshold of the metal door, knowing government cameras were watching every nuance from the telephone poles, and being nervous as I could be meeting a hero, I wondered if he really would speak with me and the well-known art journalist, Mai Yu, who accompanied us. Ai WeiWei’s young assistants greeted us and then Ai Weiwei appeared, talking on the cell phone, which is his main line to the world. He spends hours on Twitter, and before things were blocked, he put photos on Facebook by the hundreds as he recorded things that made him wonder.

|

| Sharing our hopes |

Ai WeiWei is a rather large, comfortable man in normal work clothes, who looks like a Manchu warrior, and holds on his face an appealing grin, a smile that has been through just about everything a man needs to survive. He acknowledged we were there and led us from the large patio, into his “office”, a huge wooden table on which the sun made abstract shapes. He sat right in the sun light, his new brightly colored logo as an ancient Chinese fighter, on the wall beside him. And we started little by little feeling each other out. When he smiles, he lights up the world he challenges, and he comments without restraint on how he feels about art and artists. He says over and over the role of an artist is to be an agitator, to point out corruption, pain and inconsistencies in what men say and do. Artists are not around to decorate but to install meaning and message into whatever they create so no one forgets the truth.

Ai WeiWei’s approach is to pick up historical objects and turn them into something of questionable value. For his famous Han Dynasty Urn with Coca Cola Logo, 1994, he used an antique urn and made it an artifact of modern propaganda, a tongue in cheek comment on commercialism of the rare. He made 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds – seriously – in kilns in China’s Jingdezhen Factory. He is concerned with fragments, momentary pieces. Fragments make up history, and get little credit, and in China with its billions of people, trying to move from being a fragment like everyone else, for too long content to be just a fragment of the whole, it was time for each human to stand up and be recognized as something more significant. Mao ZeTung directed everyone to be the same, to be farmers and soldiers, to work together for a common cause, the state, and there was no room for individualism or achievement. Be a stitch in the knitted state, and go along with the program dictated by the government – then you are right. Ai WeiWei, as so many of us, believes each unit, each fragment has its own personality, its own value, no matter how similar it is. This is what I interpret from his work and statements.

He was rather bundled up in a sports jacket when he greeted us, very informally. We sat down around the long wooden table – and he brought us green tea in a glass. I kept thinking to myself, this isn’t happening. My dream has come true. We talked like old friends, as if there were no barriers, and, really there were none. For once almost speechless, I kept asking, What can I do? How can I help? – which was a bit ridiculous since friends and artists all over the world have their hands reached out to him. Ai Weiwei’s only restraint is the government’s restraint on his movements outside his country. Sure, he could emigrate and leave the homeland, never to return, but he loves China and does not want to separate from it. It is his birthright. He only wants a traveling passport like anyone else, to come and go, to see and return. Yes, lots of artists are envious of the attention he seems to get, but he shares what he can and so many artists in Beijing enjoy the spaces and environments he has built as an architect in Cao Chang Di District. And growing trees are everywhere as the government planted them en masse preparing for the Olympics.

|

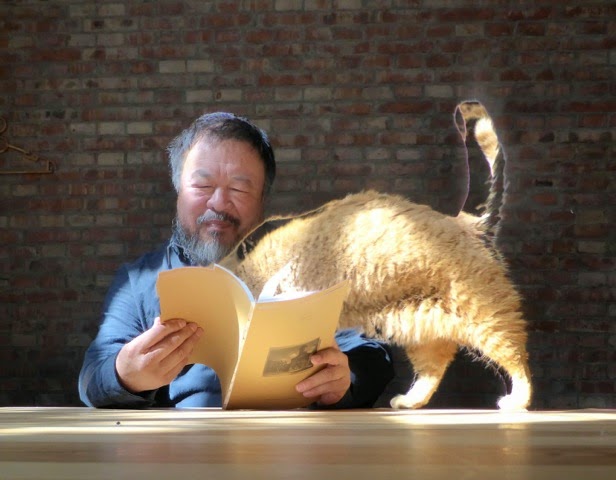

| Cats come and go |

Make no mistake – Ai WeiWei loves his country and his passion is fighting for social justice and the rights of China’s many citizens. He doesn’t aim to harm anyone nor history. He just believes that his life, and the life of any artist worth his weight, should be as critic, advocate, and defender of freedom, no matter what the medium. The artist must take risks and not wallow in success. Success is so contrary to the point. It’s the art that is. We know so much about world history because of the arts and crafts that recorded it. I think a thousand years from now, Ai WeiWei will be in the books. Once we appreciate our significance, our purpose, then contemporary artists need to re-cycle, re-structure and re-think what the past weighs upon to invigorate the future.

One of his favorite “gestures” is taking selfies with the middle finger poised in front of governmental monuments, like the Mausoleum of Mao ZeDung, the White House, the Forbidden Palace, the Eiffel Tower. I told him like all tourist I was going to Tiananmen Square the next day. He suggested I do a selfie using the same gesture. And, I did and texted the result to him. I may be presumptuous but I felt like I had joined his clan.

|

| Ai Weiwei’s bicycles |

After about an hour, Ai Weiwei’s phone was on constant buzz, since he was directing exhibits of his work in far flung places, one being the show opening in San Francisco ’s Alcatraz, the notorious cruel prison in the middle of a bay. Of course, Ai WeiWei could not travel there to put it together but his many supportive assistants heed to his word and it has been a great and curious success. So, I felt it was time we move on. He autographed a catalogue for me and then gave me two of the porcelain sunflower seeds from the installation I had so admired. What treasures those are to me. I had brought NBA Grizzlies items for his son and a bear fetish from the Native Americans, telling him for sure it was “NOT” made in China. He smiled and seem touched. It was so small an offering for such a gigantic experience.

Then his last words to me, were – “If I need to talk to God, I’ll get in touch.” It took me off guard. I hope always to be a conduit to God, and take no credit for what or who I am. I’ll never forget this encounter and pray that he will be given his passport again so his magnificent skills as an artist and an advocate, can wake up this world, especially the contemporary artists who are too much about themselves and not about others, and he could continue defending the valuable fragments that are part of our lives. God bless Ai WeiWei.

Wow – what a wonderful experience! Thanks for sharing, Audrey.