We were booked on the first flight out of Lukla at 8 in the morning, but really we were about the 8th flight because once the clouds cracked open at dawn (and we breathed a sigh of relief that the fog had gone) the charter flights from Kathmandu began to arrive, unload, reload, and fly off again to Kathmandu for the second load. There were about six of those charter flights. We hoofed it up another incline just to get to the airport, mind you, with our porters still lugging our bags on their backs. Our boarding passes had a 2 stamped on them which meant we were on the second of the returning flights from Kathmandu, second shift. It’s the weirdest flight arrangement I’ve experienced. One has to shut the eyes, ears and seat belt and just pray that the 18 others crammed into jump seats with their body sized backpacks in their laps don’t burst into a frenzy. We are tightly packed and the door to the pilot’s seat (we had a female pilot) is always opened so you can see their arms pushing and pulling on the handles hanging from the roof. We crest the steep mountains and hills under our belly, flying at about 15,000 feet, which is lower than the high to which we had trekked a few days before. Trusting God, I realized as I smelled gasoline, was the best fuel to get one to the destinat

reload, and fly off again to Kathmandu for the second load. There were about six of those charter flights. We hoofed it up another incline just to get to the airport, mind you, with our porters still lugging our bags on their backs. Our boarding passes had a 2 stamped on them which meant we were on the second of the returning flights from Kathmandu, second shift. It’s the weirdest flight arrangement I’ve experienced. One has to shut the eyes, ears and seat belt and just pray that the 18 others crammed into jump seats with their body sized backpacks in their laps don’t burst into a frenzy. We are tightly packed and the door to the pilot’s seat (we had a female pilot) is always opened so you can see their arms pushing and pulling on the handles hanging from the roof. We crest the steep mountains and hills under our belly, flying at about 15,000 feet, which is lower than the high to which we had trekked a few days before. Trusting God, I realized as I smelled gasoline, was the best fuel to get one to the destinat ion safely.

ion safely.

It was, amazingly, a relief to get back to Kathmandu. Our group posed with Jeema, the Nepali travel guy who meets us and takes care of the particulars, for photos as we all loaded into a huge van, one wider than most of the streets we would have to pass. One had to laugh at the cows laying down in the middle of the main drag. You have to go around them. They are holy. Bright violet jacaranda trees are in full bloom, and bougainvilla lazily crawls up and over just about anything in a city not very popular for trees.

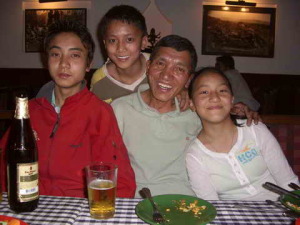

This Thursday was one of piling up laundry, reviewing what was in the bags that had been stored at the Yak and Yeti Hotel, and doing some last minute shopping. We invited Nima Sherpa to bring his three children, who live in Kathmandu to get their education, and also another Sherpa friend with his wife and the girlfriend of another of Jim’s Sherpas who is currently waiting at base camp for the summit date for Everest, and Jeta and Suka for dinner at a place where we knew we could get ice cream. It was a Nepali dinner – which means be cautious because most everything, including potatoes, is overspiced and overhot. But we celebrated the end of the trek with black orange and butterscotch ice cream. This night was the first time in almost three weeks I have slept in real sheets and with CNN humming in the background. I didn’t want night to end but at 5:30 my personal alarm clock always rings, for some reason.

Today, Friday, I had one more site to see. Kathmandu is famous for it’s Hindu crematorium. Whe n you arrive at the airport and enter the city you pass by the funnels of smoke emitted by dead bodies being cremated. Now this really was a trip out of my mind-set. Krishna, the older guide who had taken me around before, led the taxi driver (who had to hit the motor with a rock to get it started) to the most holy of Hindu Temples, resting all along a static river, called Parshu Pati Nats, which is another name for Shiva, also known as Gouri or Parvati. This place is the biggest in the kingdom and is a favorite of the caramel colored monkeys. The property is fenced in because in a small forest there are also deer. Primarily, among all the many temples honoring Shiva – the major one being centered around a giant golden bull looking like a Botero sculpture no tourist allowed so all we see is this giant gold rear end of the bull through ornate ga

n you arrive at the airport and enter the city you pass by the funnels of smoke emitted by dead bodies being cremated. Now this really was a trip out of my mind-set. Krishna, the older guide who had taken me around before, led the taxi driver (who had to hit the motor with a rock to get it started) to the most holy of Hindu Temples, resting all along a static river, called Parshu Pati Nats, which is another name for Shiva, also known as Gouri or Parvati. This place is the biggest in the kingdom and is a favorite of the caramel colored monkeys. The property is fenced in because in a small forest there are also deer. Primarily, among all the many temples honoring Shiva – the major one being centered around a giant golden bull looking like a Botero sculpture no tourist allowed so all we see is this giant gold rear end of the bull through ornate ga tes – is the site of Hindu cremation. Along this filthy river where flowers, food, monkeys, dead ashes and burned wood float, among other things, there are concrete platforms on which dead Hindu bodies are burned up on pyres. As I arrived, there was one such ceremony almost finished and another just beginning. The family brings the dead body wrapped in a bright yellow fabric – although you can see the feet – to the pyre, first walking around three times before setting it so the

tes – is the site of Hindu cremation. Along this filthy river where flowers, food, monkeys, dead ashes and burned wood float, among other things, there are concrete platforms on which dead Hindu bodies are burned up on pyres. As I arrived, there was one such ceremony almost finished and another just beginning. The family brings the dead body wrapped in a bright yellow fabric – although you can see the feet – to the pyre, first walking around three times before setting it so the  head is at the south end. The holy priest in a white shorts and top kind of outfit bustles around laying on wood and sticks, pouring holy oil over the face and then the family members do likewise, then finally putting a mixture of what Hindus consider five types of nectar in the dead mouth: honey, ghee, holy water from the Ganges, sugar and yoghurt. Then the eldest son lights the fire. Can you imagine? Women are to be left at home. They don’t participate, although there is a sort of sanctum further away where they might congregate, but burial is a man’s thing.

head is at the south end. The holy priest in a white shorts and top kind of outfit bustles around laying on wood and sticks, pouring holy oil over the face and then the family members do likewise, then finally putting a mixture of what Hindus consider five types of nectar in the dead mouth: honey, ghee, holy water from the Ganges, sugar and yoghurt. Then the eldest son lights the fire. Can you imagine? Women are to be left at home. They don’t participate, although there is a sort of sanctum further away where they might congregate, but burial is a man’s thing.

The immediate male members must shave their heads and the entire family must we ar white for 13 days after the death until they are purified. If someone dies at 5 p.m. today, they are immediately taken to the crematorium and the ceremony begins. (There’s a hospice on the grounds to make the transfer more convenient.) There is also here a special area where family mourners must live for those thirteen days, then they can return to their office job. They cannot touch anyone during that period and eat only one vegetarian meal a day. Sometimes the immediate family will wear white one year – if you see someone with white shoes, white dress a

ar white for 13 days after the death until they are purified. If someone dies at 5 p.m. today, they are immediately taken to the crematorium and the ceremony begins. (There’s a hospice on the grounds to make the transfer more convenient.) There is also here a special area where family mourners must live for those thirteen days, then they can return to their office job. They cannot touch anyone during that period and eat only one vegetarian meal a day. Sometimes the immediate family will wear white one year – if you see someone with white shoes, white dress a nd white cap, they are in that process. This is only the intimate family, not relatives in general. In three or four hours, the body, yellow marigold strewn across the corpse and then covered with the hard wood, has burned. Then the shaven headed sons who stand around and wait for it to end are in charge of pushing with a wooden rake the remaining burned wood and ashes into the holy river below. Alas, it was hard to experience. It really speaks of how transient life is and how unimportant the body is. After all we Westerners do to get in shape, imagine being burned and pushed into a rather dirty river. The water does not flow.

nd white cap, they are in that process. This is only the intimate family, not relatives in general. In three or four hours, the body, yellow marigold strewn across the corpse and then covered with the hard wood, has burned. Then the shaven headed sons who stand around and wait for it to end are in charge of pushing with a wooden rake the remaining burned wood and ashes into the holy river below. Alas, it was hard to experience. It really speaks of how transient life is and how unimportant the body is. After all we Westerners do to get in shape, imagine being burned and pushed into a rather dirty river. The water does not flow.

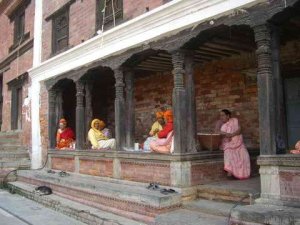

The colorful sellers of holy items surround the temple area: strings to be blessed and tied around a wrist or neck, rosary beads galore, huge boxes of powdered colored rocks which are used for blessings, and the rare rudraksha prayer beads (honestly they look like walnuts), that can be quite expensive. There is a whole hierarchy of rudraksha beads that come from trees in Nepal and Tibet and are used in both Hindu and Buddhist religions. There are 21 types of rudraksha valued for the faces or facets in each, which can be one faceted to fourteen faceted, t he rarest. The holy men say that each bead has a dark line or mukhi. If a person wishes to adopt one, they have to wash it with cow’s milk and gangajal while saying the mantra “Om Namah Shivay” on a Monday. There are rare ones joined together naturally containing the power of Lord Shiva and Parvati – it helps to improve financial problems, so it might come in handy for me at the end of this trip. A faceless one is the most powerful. Rudraksha come in sizes from a grain of wheat to that of a ping-pong ball, but the smaller is more powerful. Primarily these are the rosary beads of the Asian religions.

he rarest. The holy men say that each bead has a dark line or mukhi. If a person wishes to adopt one, they have to wash it with cow’s milk and gangajal while saying the mantra “Om Namah Shivay” on a Monday. There are rare ones joined together naturally containing the power of Lord Shiva and Parvati – it helps to improve financial problems, so it might come in handy for me at the end of this trip. A faceless one is the most powerful. Rudraksha come in sizes from a grain of wheat to that of a ping-pong ball, but the smaller is more powerful. Primarily these are the rosary beads of the Asian religions.

Photos: We are the champions, back in Kathmandu. 2) Nima, my Sherpa, and three of his children. 3) Hindu nuns. 4) Shiva’s Temple from the bull butt view (non Hindus not allowed in.)

5) Burning Hindu. 6) It’s done. 7) Holy men hanging out. 8) Powdered rock to smear on forehead or on statues.

Hi Audrey form all the McLaughlins, Demetria, Ted, Vicki, Brode, Ella, Stephan, Cori, Maddie, John and John Ryan. Sending you much love and many blessings!!!!