I miss the early mornings at Marones, the race track in Montevideo, Uruguay. We bundled in sweaters and jackets, a little fog still embracing the eucalyptus trees giving a sliver of a chill, and Sergio and I, owners of Stud La Felicidad were present as the sun rose in a haze of barrio smoke, each of us seduced by the smell of fresh dawn, and eager horses, the wildness of leather, the fried bread and expresso coffee in cups that all participants on the rail hold in their hands, or fatal cigarettes, which grooms, peons, trainers, jockeys, keep alive between teeth or fingers. In these early hours, every horse is beautiful, dusted, gallant, eager, and a possible champion, no matter what quality of pedigree, what flaw, what attitude, what condition. Everyone, trainer, groom, owner, breeder, at this hour had hope of victory. Of course, no one really knew if horse A would be better than horse B or what might impede a perfect run, even after the morning workout, which is a fast gallop at varying distances depending on the length of the race to come, the day of the week, the conditions of the track – so get out the stop watches, hug close to the rail (or get a better overall view in the stands) and believe, over and over again.

We always had six or seven runners getting ready for Saturday and Sunday cards. Excuses would soon swirl around imperfect races by any one of them. Gigolo was a hard worker at a good distance, Vieja Amiga was a sturdy filly; Hearty, coal black and hard to beat at short distance- still alive today at 23 after a long time as a breeding stallion; Prepotente, my favorite with a hopeless sway-back and two firsts. But our biggest prize was always Centaurus, the stable’s star who shot out of the gate like a bullet to race in front the entire way, hopefully: among his many stake victories, including two parts of the triple crown, he won a classic race by 50 lengths. He was close to a sure thing, but it depended mostly on the skills, behavior and “needs” of the jockey, I learned the hard way. We sent Centaurus to the states to run for the great California trainer who scouted in our part of the world, Ron McAnally. After a six month acclimatization in California, in his first USA race, our star broke his leg. End of hope.

In Uruguay, we had the “stud”, of which our race horses in training were the backbone, but we also had a “haras” or farm outside Montevideo where we sent mares to rest or be bred to an on loan imported stallion, one of the last sons of Raise a Native. Few things did I love as much as strolling into the broodmare pasture to spend a few hours bonding with the pregnant mares, hugging them around the neck and commiserating about the burdens of mamma-hood and being comfortable carrying that baby in her huge stomach. They must have enjoyed it as they’d follow me back to the fence where I’d climb gingerly and depart. The tough part was across the road was a slaughterhouse for horses, old, dreary, skinny, useless horses that somehow were tasty enough to be killed, processed and sent to France as a culinary delight. I often feared they’d stroll over and steal some of mine, fat, healthy, young colts or old broodmares. It was an legal business in Uruguay.

The world of horses has been a privilege in my life. From early days as a toddler I was plopped on the back of a shetland pony named Penny, or a mule named Mike, and was led on a walk around the extensive driveway at our vintage home on Parkway, then considered outside the city limits. Penny had double duty – carrying me and pulling a wicker carriage with seats filled with five or six toddlers at my birthday parties. When my grandfather died, and the world war died, we moved to the farm in Germantown with its pastures filled with Herefords and the stalls with fine saddle horses. Our Sunday drives, which seemed like eternities, were to the farm, the six plank white fences announcing we were close and as the car passed through the two white brick posts, we could see the primary horse barn, white brick with a green roof and giant doors at the north and south ends. It was probably the largest in the South at that time, paneled with fine wood, 33 stalls sufficiently large to house giant Clydesdales, and above the rows of stalls on each side of a long workout strip was the hay loft, a mysterious and intriguing place my brother and I dared to explore, watching out we didn’t stumble into the feed shaft. The grooms would lift up a wooden panel and dump a bale of alfalfa down into the stall. There were steps up to the loft and also ladders at each end of the long barn that seemed to us as if they would reach to heaven.

The world of horses has been a privilege in my life. From early days as a toddler I was plopped on the back of a shetland pony named Penny, or a mule named Mike, and was led on a walk around the extensive driveway at our vintage home on Parkway, then considered outside the city limits. Penny had double duty – carrying me and pulling a wicker carriage with seats filled with five or six toddlers at my birthday parties. When my grandfather died, and the world war died, we moved to the farm in Germantown with its pastures filled with Herefords and the stalls with fine saddle horses. Our Sunday drives, which seemed like eternities, were to the farm, the six plank white fences announcing we were close and as the car passed through the two white brick posts, we could see the primary horse barn, white brick with a green roof and giant doors at the north and south ends. It was probably the largest in the South at that time, paneled with fine wood, 33 stalls sufficiently large to house giant Clydesdales, and above the rows of stalls on each side of a long workout strip was the hay loft, a mysterious and intriguing place my brother and I dared to explore, watching out we didn’t stumble into the feed shaft. The grooms would lift up a wooden panel and dump a bale of alfalfa down into the stall. There were steps up to the loft and also ladders at each end of the long barn that seemed to us as if they would reach to heaven.

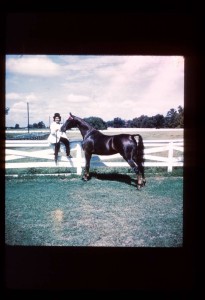

At age six, after we moved to the farm in 1946, life as an equestrian began. My mother, from Rhode Island, and my father, from Memphis, met at the Devon Pennsylvania Horse Show and blended their champion stables of American Saddlebred horses. At that time, in the ‘30ties horse shows were popular, usually held in conjunction with state and county fairs and to raise funds for charity. In Shelby County, the Saddle Horse families included the Pidgeons of Magnolia Farms, the the Wrapes of Gregnon Farms, the Burch family, and the Taylors of Wildwood Farms. The leading trainer was Paul Raines, who we constantly battled against. Our trainers began with Garland Bradshaw, then Eddie Barham, then Eli Long Jr, all well known for putting top horses in the ring. The dirt floor of our showplace barn was covered in crushed pecan shells, good for the horses feet. It was the perfect training barn as a saddle horse could get a good trot, canter or rack in going down one side, which was about 4 tenths of a mile but seemed like forever if I was riding a horse I couldn’t control.

At age six, after we moved to the farm in 1946, life as an equestrian began. My mother, from Rhode Island, and my father, from Memphis, met at the Devon Pennsylvania Horse Show and blended their champion stables of American Saddlebred horses. At that time, in the ‘30ties horse shows were popular, usually held in conjunction with state and county fairs and to raise funds for charity. In Shelby County, the Saddle Horse families included the Pidgeons of Magnolia Farms, the the Wrapes of Gregnon Farms, the Burch family, and the Taylors of Wildwood Farms. The leading trainer was Paul Raines, who we constantly battled against. Our trainers began with Garland Bradshaw, then Eddie Barham, then Eli Long Jr, all well known for putting top horses in the ring. The dirt floor of our showplace barn was covered in crushed pecan shells, good for the horses feet. It was the perfect training barn as a saddle horse could get a good trot, canter or rack in going down one side, which was about 4 tenths of a mile but seemed like forever if I was riding a horse I couldn’t control.

My inaugural horse show was in Humboldt, Tn. Strawberry Festival, when I was eight years old, where I won first place in the pony class on White Socks, a push button type of pony who reacted to the orders announced over the loud speaker – walk, trot, canter. I just sat there in my riding suit, Daddy’s necktie, jodhpur boots and black derby while White Socks did the work and we usually won. She had four white stockings with black dots on them and was roundly fat, as was I, and we made quite a pair. I remember when mother took me to the farm to try her out before purchase. Of course I didn’t know about those kind of things, and was more worried about whether I would fall off, since I was still new at horse showing, as they called it. It was special to have horses in those days and my failure at popularity at school changed when the word got out I had horses.

The first Germantown Charity Horse Show began in 1947 with Emmet Guy as show manager, and Berl Olswanger at the piano giving a beat for horses and ponies to follow as they preformed in the ring. I took piano lessons from Mr. Olswanger, so he usually picked my pony’s step rhythms to set the beat of his song. But the favorite class for spectators at the annual Germantown Charity Horse Show was the Costume Class, in which I participated, the first year, as a peasant with baskets of flowers and riding my pony Penny. We won second. In subsequent years, I gathered up the kids on the farm and created floats with themes from Wizard of Oz, to African Jungle (putting a black and white sheet over White Socks to make her a zebra )and we won the silver cup a couple of times. It wasn’t easy. My mother was a popular exhibitor with her fine harness (horse drawing a special buggy), three-gaited and five-gaited horses – which were called “shaky tails” by people who thought they were funny. On the other side were hunters and jumpers and of course Tennessee Walking Horses, who at this time in history, were victims of all kinds of adjustments to their feet and legs to make them lift their hooves high as possible. The house safe was thick with silver trophies, trays, pitchers, and casseroles won in competition.

The first Germantown Charity Horse Show began in 1947 with Emmet Guy as show manager, and Berl Olswanger at the piano giving a beat for horses and ponies to follow as they preformed in the ring. I took piano lessons from Mr. Olswanger, so he usually picked my pony’s step rhythms to set the beat of his song. But the favorite class for spectators at the annual Germantown Charity Horse Show was the Costume Class, in which I participated, the first year, as a peasant with baskets of flowers and riding my pony Penny. We won second. In subsequent years, I gathered up the kids on the farm and created floats with themes from Wizard of Oz, to African Jungle (putting a black and white sheet over White Socks to make her a zebra )and we won the silver cup a couple of times. It wasn’t easy. My mother was a popular exhibitor with her fine harness (horse drawing a special buggy), three-gaited and five-gaited horses – which were called “shaky tails” by people who thought they were funny. On the other side were hunters and jumpers and of course Tennessee Walking Horses, who at this time in history, were victims of all kinds of adjustments to their feet and legs to make them lift their hooves high as possible. The house safe was thick with silver trophies, trays, pitchers, and casseroles won in competition.

Life on Wildwood Farms meant every day there were horse encounters. I could go down to the barn and ask to ride Spot or Alec, farm horses, and more normally, I had to exercise my pony or whatever horse I was learning to ride for upcoming show seasons. There was no play or petting time with the fancy horses. They weren’t like dogs that followed me around. I couldn’t feed them nor brush them because I’d probably move the hair the wrong way. I often hung on the fence around the pastures outside, hoping a horse would come up and blow on me with her nose. Then I could pull some weeds and feed her to keep her attention, or just rub her under the chin and talk to her.

The most exciting days were when the Budweiser Horses arrived in those enormous 18-wheeler trucks to spend the night on their way back to St. Louis. Daddy was friends with the Busch and Orthwein families and we were the only one on their travel route with stalls large enough for them to be comfortable and safe, thanks to my father who designed and built the main barn. Once golfer Gary Player visited with intent to copy the barn for his horses in South Africa. But for me, when superstar horse Wing Commander came to spend the night on his travels, that was as if LeBron James or Payton Manning had come for dinner. Wing Commander, owned by the top saddle horse stable in the country, Dodge Stable, was the leading saddle horse breeding sire, after many victories in the ring. His rider had always been Earl Teater.

In the 50ties we were the site for the a steeplechase on the southern circuit that even today includes races in Maryland, Virginia, Tryon, N.C. and the Iroquois Steeplechase in Nashville. The farm’s fields would be transformed into natural jumps, flowers decorated each one, and on race day crowds would fill up pastures with their cars. I loved this event and even had an early crush on a jockey in the races, although I was still too young for boy friends. The steeplechase was short lived. I don’t think Daddy liked having the pastures torn up, for the aftermath of race residue was a major clean-up, and we still had a barn full of saddle horses that required care and attention.

In the 50ties we were the site for the a steeplechase on the southern circuit that even today includes races in Maryland, Virginia, Tryon, N.C. and the Iroquois Steeplechase in Nashville. The farm’s fields would be transformed into natural jumps, flowers decorated each one, and on race day crowds would fill up pastures with their cars. I loved this event and even had an early crush on a jockey in the races, although I was still too young for boy friends. The steeplechase was short lived. I don’t think Daddy liked having the pastures torn up, for the aftermath of race residue was a major clean-up, and we still had a barn full of saddle horses that required care and attention.

Summertimes we usually spent a month at a dude ranch in Colorado (C Lazy U) or in Wyoming (GP Bar Ranch) and there I could become whatever I wanted to be, so I usually signed up to help the wranglers at dawn to round up the horses that were put out on the mountains at night, and then I could sling a western saddle over their backs to help get them ready for the dudes’ daily mounts. I rode a pinto named Angel. She was really a dude horse. Buy I also set a goal to ride every horse, about 50, at GP Bar Ranch, be it work horse or freshly broke colt. And I did it, without falling off. And I wanted to take about a half dozen home. But we didn’t mess with dude ranch horses. Every day we rode up and down some sort of peak, through a creek that required the horse swimming at some point, or slipping and sliding on rock, and what saved legs and feet were jeans, leather chaps and cowboy boots, which we lived in of course. For a few weeks, I exercised my side dream to be a cowgirl, and ate with the cowhands huge breakfasts with bacon,eggs and biscuits, which wasn’t considered girlie. Lunch on a ride was something out of a sack, sandwiches, a fruit, a cookie. Leave nothing for the moose or bears. I never considered myself a skilled equestrian, but often on the ranches, they’d put me on a rather problematic horse to calm him down before he would be turned over to a guest. It was a skill my father had. Maybe I inherited some of it.

Our own Wildwood Farms was in fox hunting country, and that meant on weekends there was a herd of horses cantering and jumping of fences with packs of beagles barking up a storm, leaders wearing red jackets and hooting to the dogs as they tried to catch up with the feisty fox. I don’t know if they ever did. I didn’t know how to jump jumps on horseback, although when I was at junior college in New York, I was placed in the horse program and learned how to jump somewhat. However, on returning home for winter break, I was determined to show my mother I had learned to jump, and mounting Patchwork, the sort of jack of all trades pony, we set out to the ring where there were a couple of practice jumps – low ones – and as I galloped properly toward the fence, Patchwork leaped across beautifully and landed on the other side, I was not with her, but on the ground. My jumping days were done.

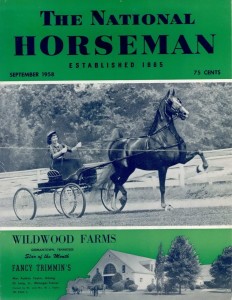

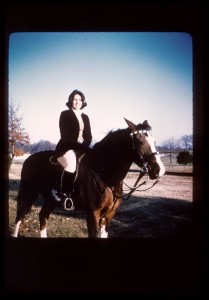

I was never allowed to play with the glamorous show horses. I wasn’t allowed to go down to the barn and saddle up even my own pleasure horse, like most girls did. I’d have loved to brush and clean my own horse and feed and worry about just one. But, we had grooms that did that and Mother didn’t want me to mess up a horse that might be sold for a price. It was all about the business, I was told. When my daughters fell in love with horses, I put no restrictions on them because I knew the joy of being able to kiss a soft nose, pull at the amazing ears, cleaning their hooves, and riding at ease on their backs going no where much, hugging them around their necks, and rubbing them dry after a bath. It is important for a young girl to be passionate about her own horse. The saddle horses were a business, everyone insisted and the whole point was to get them sold. There were photo sessions frequently, and once I was on the cover of The National Horseman magazine, not because of me, but because I was sitting in the buggy driving Fancy Trimmings, the champion fine harness horse.

At the end of the 1950s, after we had won regional championships, although we never were victorious at Louisville where the toughest championships and Stakes for saddle horses were held, polo began to rouse its head in our area and with me being away most of the time at boarding school and then college, mother decided to sell all the saddle horses and turn to polo ponies, which had become the delight of my brother Lee, and my father. It was fun for all of us and friends accumulated for the sport came from all over the world. We even held the National Open Polo Tourney once when there were problems in Oakbrook, Ill, where it was usually held. The best of the best housed their ponies in our long barns, and I was able to get a job as a morning galloper, three horses at a time on a lead line. I exercised horses alongside the great Harold Barry and Jackie Murphy. And also made homemade biscuits for the grooms and polo visitors as Virgie Christian and I prepared outdoor breakfast from his chuck wagon each morning of the tournament. Normally, cowboys were major participants in polo.

There was a constant coming and going of players and truck loads of horses. People passed through on the way to elsewhere and joined in our weekend polo games or turned their stock out to pasture on our farm, where the winters weren’t so severe. There grew a whole new garden of friends, solid folk who wore Lucchesi polo boots and team caps who would each day visit my dad when he was home from the office to talk about polo. Dad might play a chukker or two, but he was known for being a brutal referee where no one got away with anything. He even purchased a stable at Lake Worth, Fla. with Stuart Igleheart so my brother could play there in the winter. Polo and its characters were the biggest pleasure in my father’s life, along with tennis, at which he had a classic elegance. Only once my father dared to leave the USA, to go to the Open polo in Argentina. It was a complete disaster as it rained so hard all the matches were cancelled and the hotel did not have Kleenex, which upset my father. He never left the US again. But the love of the people brushed off on me. Traveling with the guys, I had to develop the courage to wear jeans and boots on an airplane. And as guest of polo fan, Mrs. Boehm (of the porcelain fame) I even attended the Queen’s Cup in England when Lady Diana was very pregnant with William. She drove herself to the match to watch Prince Charles play. I was close by. And in awe of her freedom.

There is little that soothes me like spending time with a horse. My family has been so uber horses, I stayed in the background until I had my own stable in Uruguay and could spend an afternoon wandering the pastures filled with broodmares busting with offspring. Having birthed three of my own, I could commiserate with their giant bellies, and their sort of peaceful acceptance of what was about to happen. I have had milestones – like going to Arkansas to see Zenyatta, truly the most stage-spectacular racing horse I’ve seen, as she pranced to the gate and took charge; and I’ve ridden buggies drawn by the breath-taking black Freison horses, among the oldest breed still going from Hadrian’s day, their black manes and hairy feet and classic bent neck as they prance along the road take a big place in my memory. One of the most painful moments was in Tibet when I had to ride a pony not much bigger than a carousel horse up a steep, rock-jammed mountain, frozen in ice as well, as I took the challenge to circumnavigate Mt. Kailash in a spiritual pilgrimage. The poor pony stumbled and fell and I was frightened and angry that I was hurting him by being on him in a strange saddle. Reaching the top of the incline, carpeted in prayer flags,I was able to dismount and the pony was free to descend the mountain without my clumsy weight, as I had to slide down the slippery slope.

There is little that soothes me like spending time with a horse. My family has been so uber horses, I stayed in the background until I had my own stable in Uruguay and could spend an afternoon wandering the pastures filled with broodmares busting with offspring. Having birthed three of my own, I could commiserate with their giant bellies, and their sort of peaceful acceptance of what was about to happen. I have had milestones – like going to Arkansas to see Zenyatta, truly the most stage-spectacular racing horse I’ve seen, as she pranced to the gate and took charge; and I’ve ridden buggies drawn by the breath-taking black Freison horses, among the oldest breed still going from Hadrian’s day, their black manes and hairy feet and classic bent neck as they prance along the road take a big place in my memory. One of the most painful moments was in Tibet when I had to ride a pony not much bigger than a carousel horse up a steep, rock-jammed mountain, frozen in ice as well, as I took the challenge to circumnavigate Mt. Kailash in a spiritual pilgrimage. The poor pony stumbled and fell and I was frightened and angry that I was hurting him by being on him in a strange saddle. Reaching the top of the incline, carpeted in prayer flags,I was able to dismount and the pony was free to descend the mountain without my clumsy weight, as I had to slide down the slippery slope.

Still on my bucket list, however, is the Kentucky Derby.

One daughter lived on her horses, loved them, took care of them, learned dressage, learned to jump and hunt and feel at ease on horses, and passed this on to her children, who went to pony club and rode in juvenile jumping classes, and did well. My oldest daughter had terrible allergies to horses and hay and grasses, although she was an excellent equestrian at an early age. My son actually played polo and was captain of the Polo Team at University of Virginia. My mother continued to be a Grand Dame of the Germantown horse world until she died. And many of our family friends are still active in the polo world, so we watch matches in the large playground of south Florida’s horse world. My late brother was married to a popular equestrian who won a gold medal at the Los Angeles Olympics. She is still a commentator for international equestrian events and still lives on the farm, close to that amazing barn, and with all the memories of our lives still stomped deep within the soil.