The King is Dead.

Headline setters brought out giant type for that. Elvis in his mortality, bigger than life, but too obvious as he aged, was supposed to be forever. He had the makings of the classical tragic hero like Hamlet. Now in death, God’s amazing grace had rescued a rock that was falling.

The morning of Elvis’ earthy death, I sat at my desk on the fifth floor of the Memphis Publishing Co. Elvis memories began to soar around the room like a giant bumblebee in heat. Remember Russwood Park? Remember his Harley? Remember his super-beautiful wife a bit over-appliqued with makeup and hair hives? Remember this. Remember that.

There was much activity in the newspaper office that moment, since my daily got the “scoop”. Tears were tearing up even in tough guys. Some laughed at the fuss, didn’t sympathize with the King at 40, a fat and drugged has-been, they said. But most of us admired this man who put Memphis on the map and old photos and stories were resurrected for a special edition of the evening newspaper. I kept my story to myself. I wasn’t really part of his circle or knew him or had much to remember, but what I had was mine.

Many years had passed since Elvis first fired up the hearts of my confused generation. I could have been the first Elvis impersonator. In St. Catherine’s boarding school (11th grade) in 1955 I was elected to direct the “new girls” show. Hailing as I did from Elvis’s hometown, and having a true Elvis duck tail haircut, it was sequential that I do a mock Elvis skit. I looked a bit like him, fleshy, oval face, not much chin, right side of the lip curled up easily, eyes that drooped at the outside corners, black hair and ability to swivel the hip.

So in a man’s black suit, borrowed from the drama department wardrobe, and adding a wide stripe shirt in pink and black with open collar, I pointed my loafered toe in a twist and took off for fame while mouth-syncing the words to “Don’t Be Cruel to a Heart That’s True. “(I knew this by heart because mother woke us up with that song every morning of summer vacation in Cape Cod.) From then on, my name in this Episcopal girl’s school in Richmond, was “Elvis.”

But there is more.

It was at this time Elvis moved into a green single story home in Audubon Park. The neighborhood flinched, except for the multi-millionaire families who lived in two huge estates that backed up to his middle class house. The Butlers had one, and Hugo Dixon the other. The Butler’s son Landon, was my brother’s best friend, and somehow, he had arranged for my brother and me to go to Elvis’ house just to meet him. It was sort of an early pilgrimage. With the singer’s first gold record already on the wall, Elvis had just received a healthy contract with RCA. But as yet, no one was sure of his greatness. This was also before “sex appeal” was a public topic. We just didn’t talk about sex. It was not a proper word, much less a whole lot of shaking going on.

In 1955, no one knew this man would have the same impact in the world of entertainment as Babe Ruth had had on baseball. Elvis came from the sticks with a swagger and a sound never to be equaled, but often imitated. This June, in the mid-fifties before it all exploded into fame, there were no crowds up and down Audubon Street, no autograph books waving up like palm fronds, no “when will he come out” vigils.

And so one evening in summer, we went there, the three of us. At 16, I had a special driver’s license, so my brother and Lanny, both 14, urged me to drive. After pulling up to the sidewalk, we walked up the short drive, filled with Elvis’ blue Cadillac, and a new three-wheeled car, and just walked in the front door.

It was a sticky delta night. Air conditioning was not common, so the door was open, entry protected only by a screen door against which mosquitos flattened themselves. Elvis’s momma, Gladys Presley, in sort of a floral house dress and her face swollen from sickness, was resting in a big arm chair. She nodded her head to us like two neighbors passing on the dirt road:

“Come on in”, she said effortlessly.

I’m sure she didn’t know who we were, why we were there. Was she even aware of what was to come? Already she must have sensed people were drawn to her son because of his homemade voice, good looks and earnest song.

Elvis in a black silky shirt, opened to the chest, was bent over a pool table, a shock of hair hanging in space in front of his forehead, cue stick on the ball. He was alone. Silent, concentrating. A couple of cloth chairs were pushed back against the wall, but I was afraid to sit. We wouldn’t stay long. The light was dim, probably to keep the light-loving insects at bay.

There was kind of a green feeling to the room. Somehow I was embarrassed that we were there. I didn’t want to look at anything, to take notice of how he lived or where things were. I could tell right off his home didn’t have the same ambience as my home. So, not wanting to appear curious or disrespectful, I kept my eyes down. Did Lanny really know this person? Was it okay to be here? There was no welcome effort on the Presley’s part. My parents would have been furious at us, if they had known. What we were doing was tacky, in bad taste. Like most parents at that moment, they weren’t too sure about rock-n-roll music anyway. Many thought it was devil-sent.

I did notice that Elvis’ hair wasn’t greased. His eyes were what Adam’s eyes must have been, full of life but already sadden by from where he had already struggled and what destiny he had to do, as if he had any choice. When Elvis poked the cue stick and hit the net pocket with the red ball, he smiled and noticed we were there. He made a joke. We laughed very lightly. I liked Elvis because of his humor. He tried to ease the situation with teasing, like at press conferences, or to the public, and eventually on stage in the final days when he knew he couldn’t hack it, but was going to go on anyway, throwing scarves of his sweat to the hands reaching out like cactus spines below him.

“Want a coke? “ the music messiah asked politely. He liked Coke-Cola best and was halfway into the bottle of one.

“No thanks”, we said nervously. Were we ashamed that he offered us something? Were we aware of our intrusion? Were we just not thirsty?

But in the silence of his playroom, there wasn’t much to signal what was to come. And we sort of got bored, just sitting there watching Elvis play pool by himself, especially since we didn’t know how to play pool. So we left, sort of just leaving as we had just come in, unnoticed, and went to Tropical Freeze to get a soft ice-cream cone, the twirled one that looks like thick paint.

The next day, wearing this Elvis accomplishment in my heart – that we had been in his home with him – I just had to drag my best friend to the place where I had been. We just planned to drive by, since Adrienne had never seen his home. The two of us stood out from our classmates for one reason: our cars. Her father, a car fancier, had given her a turquoise blue Thunderbird when she turned 15. My father had given me a canary yellow Chevrolet convertible with black top. Sharp, it was. You could see it coming. And it was the only car in the history of the Taylor car stable that was not black.

Top down, music on the radio (no tapes in those days) we put on our pedal-pusher pants and drove in to the city from our farms in Germantown (where we lived). It was a Saturday. And as we drove in automatic gear down Audubon Drive, arriving quickly at our destination, there was Elvis in a pink and black shirt of abstract forms, and a couple of his buddies, likewise sporting greasy mock-ducktail hairdos, black sunglasses, gold rings and Lansky Brothers shirts, coming out the front door.

Wow. Stop that Car! And Elvis cruised his eyes over my yellow vehicle as he grabbed the door-handle of his powder blue Cadillac, also with top down.

“Hey, honey, “ he said with a jingle in his eyes. “How ‘bout a trade?”

“Sorry Elvis, I like mine better,” I reply. And I did. I still don’t like Cadillacs.

But I was so shook up by the chance meeting, I sort of lost consciousness for a moment. Here was my chance to say something clever, and I flubbed it. Among all the cars collected in his career, Elvis never chose a Chevy, considered in the lower ranks of General Motors, which was, at that time, in the hands of my cousin Alfred P. Sloan. It might have been a first if I had traded with him.

“Some other time, then,” he finished. And got into his car. We, out of breath, but giggling, drove off, laying a little wheel-rubber to impress. He looked much handsomer in the daytime. Elvis, his arm hanging over the door of his Cadillac, followed us at least to the stop sign at Park Ave, where he took a left.

———-

Five years later, Elvis was everywhere in the media. Ever since Russwood Park’s concert, Memphis had grown obsessed about something in a way it had never been before. Elvis had purchased Graceland in the South Memphis area of Whitehaven. His mother had passed and his father already connected to another woman, Dee Elliot. Every little word, every movement of the now rock and roll king was hot news.

In 1960, I was a fledgling intern on the Memphis Commercial Appeal, the morning paper. There weren’t any women assigned to City Desk then, but I was. Females were herded to the society department where an uptown wedding could take up a whole page. And engagement announcements got the same amount of space as a war story, or an Elvis vignette.

On this June day, an Elvis story was breaking. I was in the middle of compiling a dutiful but never insignificant obituary. Malcolm Adams, city editor, his cigarette permanently pasted on his lower lip, yelled:

“Go out to McKellar Lake. Barney (Sellers the photographer) will take you. Elvis has a new boat. See what you can get.”

I guessed this was a mini-scoop, although it wouldn’t make a difference to national politics. I remembered the night at Russwood Park. I had been there, pulling back from all the screams and fainting girls in undershirts. I didn’t want to be part of that. It frightened me, like seeing pilgrims kissing the statues of Virgin Mary. Elvis was so alive. He knew how to play the crowd, to braid them into a knot, then let them loose again, having gotten a bit of wave in them. His phenomenon was in charge. Police, who had known him as a friendly good guy who liked motorcycles, got tense when Elvis began to move moaning masses like a Moses on the Exodus. This was a first for crowd control in my town. A worry. A controversy.

But this day my journalistic challenge was to see Elvis’ new toy, a speedboat. It was just as important as that concert where we saw sex raise its pre-pill power. (The birth control pill arrived after the Elvis phenomenon.)

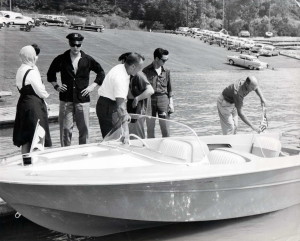

“Elvis Presley, in a yacht man’s cap, bought a speedboat. He’s pleased with both,” the photo caption would read. We caught the rock and roll King and five friends climbing into the 75 HP runabout at the unstable McKeller Lake dock, stirred up by the choppy muddy waters of the Mississippi. The boat was the same color as Elvis’s very first Cadillac – powder blue. As the King grew, so did his collection of machines.

Elvis was dressed in a black sea captains hat, black suede shoes with silver buckle, gray pants, and a black shirt, partly opened at the chest. He was comfortable, but didn’t appear too keen on a reporter being there, even though she was female. He was moody and not interested in conversation. He hardly smiled except when Barney had him in focus. “Guess I ‘d better take off my specs,” said the rhythm king as he slid behind the wheel of the 16 foot craft. On the floor of the boat was a pair of water skis.

I felt like I was taking down trite stuff. There wasn’t much to this outing. I guessed he was tired, because already his life had taken on the aura of a superstar. It was sad. To be able to enjoy anything, Elvis had to rent out the fairgrounds or a movie theater during the night hours to escape relentless public adoration. The gates of his mansion were solid with female fans wanting to get a kiss. There was a never-ending presence of swarms of admirers at the entrance, along the wall which had to be re-enforced often, and on both sides of the street. Luckily, the fans didn’t know about his being at McKeller Lake with a new boat or it would have been chaos.

.

With an expensive roar, Elvis and his speedboat zipped from the dock in a brown spray for a trial run. He’d learned the mechanics back in Hollywood where he first got inspired to own one. I asked him how it went. Elvis replied, “Uh, huh, pretty good.” When he was buying the craft, only one passerby had noticed Elvis in the store and was so overcome with excitement, she drove her car right through the window.

Later, I interviewed Elvis about another purchase, a pink surrey with a fringe on top, It was actually a recycled World War II jeep illuminated by bright colors and canopied with frills, fringes, and rolled up curtains. Then when the first commercial jet landed at the Memphis airport, he set his sight on having a jet in his collection, which he did. This man craved moving machines like he collected panda bears, motorcycles to whip through Memphis streets, horses to gallop around his property; he liked slapping waves with his boat, wrecking his pals in the dodgems, and riding the fragile looking pippin at the Fairgrounds. “Gives me something exciting to do,” he admitted.

Years later, on my way to work at the newspaper before dawn, I often encountered Elvis, well hidden in helmet and black leather gear, filling up his motorcycle at the same Exon station I used on Poplar Ave. Soon after, he died from an overdose of medication. The Elvis we had come to know had lost his old flare by aging too fast, trying to live the cycle he had to live as a celebrity superstar. There was no room to breathe. I’m glad I saw him in the simple times, and get nostalgic when I hear his songs, now as famous as the National Anthem. No one else has been quite like him, nor turned quite the page of life and fame as Elvis did. Thank God for his spirit and faith and love of Memphis. Now, he has truly left the coliseum, the closed one at the Fairgrounds where he first began in the ‘50s.