Chartreuse flowered dogwood trees with green seeds in the middle of the four petals, blue poppies in  remote ranges, exotic orchids by the hundreds hiding out in thick pine and cypress forests hanging with moss, there is a world of horticulture that Bhutan citizens augment by their own interest in roses and potted flowers.

remote ranges, exotic orchids by the hundreds hiding out in thick pine and cypress forests hanging with moss, there is a world of horticulture that Bhutan citizens augment by their own interest in roses and potted flowers.

I had never seen green dogwood flowers until visiting the private residence of one of Bhutan’s most favored Lamas, who has been declared the ninth re-incarnation of Datong Tulku, who was the incarnation of Bami Yeshi Yang, one of the seven monk disciples of Guru Rinpoche, who brought Buddhism to Bhutan. Incarnation is based on certain chosen people being able to remember and to identify objects and events in a previous life. It’s complicated, it’s cuious, but Lama Datong Tulku is just straight out a nice, cheerful man who gives a warm welcome to strangers. He is known as the “Laughing Buddha.” Lama Tulku with his Bishop-like miter, does efface a smiling Buddha, with red stain on his teeth caused by chewing beetle tree leaves smudged with limestone, a common habit in Bhutan. (Beetle leaves and chili peppers are national favorites.)

tures on this trip, I find there are many similarities in all religions, such as the use of holy water for cleansing (in our baptism, in Jewish rights, and in Buddhist and Hindu traditions.) Rivers such as the Ganges in India and the Jordan in Israel and streams that pop out of mountains without mouths take on curative powers, be it their water or their mud. Maybe we should re-think the Mississippi.

tures on this trip, I find there are many similarities in all religions, such as the use of holy water for cleansing (in our baptism, in Jewish rights, and in Buddhist and Hindu traditions.) Rivers such as the Ganges in India and the Jordan in Israel and streams that pop out of mountains without mouths take on curative powers, be it their water or their mud. Maybe we should re-think the Mississippi.  for ceremonial regularity. On his elaborately painted desk was a metal vase with a peacock feather fan. The peacock is a bird who can eat poison and survive, the Lama explained, therefore the feathers symbolize the peacock taking away all poison that might be damaging a person’s heart and soul and body. Beside it was a bronze bowl of dried rice, often tossed during the ceremony along with seeds from jacaranda pods, and a yak butter candle sculpture, which was slowly melting, having been lit. All was ready for us.

for ceremonial regularity. On his elaborately painted desk was a metal vase with a peacock feather fan. The peacock is a bird who can eat poison and survive, the Lama explained, therefore the feathers symbolize the peacock taking away all poison that might be damaging a person’s heart and soul and body. Beside it was a bronze bowl of dried rice, often tossed during the ceremony along with seeds from jacaranda pods, and a yak butter candle sculpture, which was slowly melting, having been lit. All was ready for us.  nderneath him and he said lamas and monks grow accustomed to that in childhood. I guess it’s like me sitting in a chair with my legs crossed.(Incidentally the future Buddha manifestation – yes, Buddhist believe Buddha will come again in another form recognizeable – sits Western style on a chair. Hmm.) There were two monks assisting and all three began to chant the Buddhist scriptures in a deep guttural hum. I sat beside the Lama on the floor since I was the principle character in this ceremony. My friend Sonam, an elegant Bhutan lady, instructed me on how to do things during the ceremony. Then when we were asked to repeat after the Lama certain words from the scripture asking for blessings I tried to repeat him just listening to sound. I knew nothing about what it meant, but trusted it fit in with my omnipotent God’s spirit. W

nderneath him and he said lamas and monks grow accustomed to that in childhood. I guess it’s like me sitting in a chair with my legs crossed.(Incidentally the future Buddha manifestation – yes, Buddhist believe Buddha will come again in another form recognizeable – sits Western style on a chair. Hmm.) There were two monks assisting and all three began to chant the Buddhist scriptures in a deep guttural hum. I sat beside the Lama on the floor since I was the principle character in this ceremony. My friend Sonam, an elegant Bhutan lady, instructed me on how to do things during the ceremony. Then when we were asked to repeat after the Lama certain words from the scripture asking for blessings I tried to repeat him just listening to sound. I knew nothing about what it meant, but trusted it fit in with my omnipotent God’s spirit. W e frequently said “she she she” and that means “please please please.”

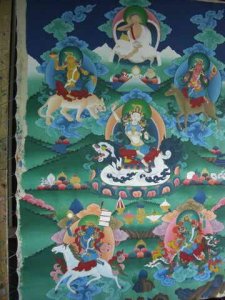

e frequently said “she she she” and that means “please please please.”  etween woodworking or doll making or Thangka painting or embroidery or weaving, among other crafts, and serve out a four to six year apprenticeship. The next step would

etween woodworking or doll making or Thangka painting or embroidery or weaving, among other crafts, and serve out a four to six year apprenticeship. The next step would be to work decorating houses and wood or in one of the textile enterprises where women sit on the floor, barefoot, and weave fabrics for national dress. A simple pattern would take about two days. A complicated colored pattern with an embroidered effect, takes over a month on back strap looms, is much more expensive, and the weaver can earn one fourth of the selling price. The faster the weaver, the more fabric she can turn out, the better her pay.

be to work decorating houses and wood or in one of the textile enterprises where women sit on the floor, barefoot, and weave fabrics for national dress. A simple pattern would take about two days. A complicated colored pattern with an embroidered effect, takes over a month on back strap looms, is much more expensive, and the weaver can earn one fourth of the selling price. The faster the weaver, the more fabric she can turn out, the better her pay.  ups of tall poles of mostly white vertical prayer flags, 108 in a group, honoring the dead. Colorful prayer flags are draped at inopportune places (you wonder what fool crawled across open crevices and in giant trees to string them up) as well as at religious sites. When we arrived at a the Amanakora Punakha hotel, we were presented with prayer flags which we were asked to hang on the suspension bridge, the only way to cross the river to reach the small r

ups of tall poles of mostly white vertical prayer flags, 108 in a group, honoring the dead. Colorful prayer flags are draped at inopportune places (you wonder what fool crawled across open crevices and in giant trees to string them up) as well as at religious sites. When we arrived at a the Amanakora Punakha hotel, we were presented with prayer flags which we were asked to hang on the suspension bridge, the only way to cross the river to reach the small r esort. As a gift there was a roll of prayer flags and incense on my pillow that night with this message: “Although there are only 700,000 Bhutanese millions of prayers and blessings are released into the world each day from the fluttering of the prayer flags each turning of prayer wheel and the silent mantras sent to the heavens on incense smoke. The horse at the center of your prayer flags is called the Lungta, the wind horse. It rides the winds of the world carrying blessings and protection to all those whom the wind touches.” Long live horses and prayer. They’ve certainly been cornerstones for me.

esort. As a gift there was a roll of prayer flags and incense on my pillow that night with this message: “Although there are only 700,000 Bhutanese millions of prayers and blessings are released into the world each day from the fluttering of the prayer flags each turning of prayer wheel and the silent mantras sent to the heavens on incense smoke. The horse at the center of your prayer flags is called the Lungta, the wind horse. It rides the winds of the world carrying blessings and protection to all those whom the wind touches.” Long live horses and prayer. They’ve certainly been cornerstones for me.