In Punakha, Bhutan, there is another wonder of the world. It makes St. Peter’s of Rome seem dull.

The winter Dzong which houses the Lama who is overseer of all religion for the citizens of Bhutan – a position of equal power to that of the King who is master of government of the people- is one of the most extraordinary works of art and architecture I have ever seen. The ornate tall and multi-leveled white structure housing probably the most powerful temple and its adm inistration headquarters in this country, sits where two large rivers converge (referred to as the male and the female rivers) and is approached by a cantilevered wooden bridge, equally decorated with the traditional wooden window and columnar decor of Buddhist architecture..

inistration headquarters in this country, sits where two large rivers converge (referred to as the male and the female rivers) and is approached by a cantilevered wooden bridge, equally decorated with the traditional wooden window and columnar decor of Buddhist architecture..

In the style of Bhutan homes, where the lower floors are used for storage of food supplies, animals, and equipment, this sample of glory rises up probably fifty feet to open roofs under which herbs and grasses are normally dried and birds dare to hide out.

But in this structure with its giant public squares where religious activities are held, the whopper experience is entering the temple where monks study, pray and sometimes eat. This room is held up by 40 gold plated columns embossed with dragons and on the north wall are statues of Buddha Sacamani (in his present form), Guru Rimpoche who brought Buddhism to Bhutan in 746, and Sheptrung, who unified Bhutan in 1600. Each figure, at least three stor ies high, is shrouded in gold brocade capes and is gilded gold. Buddha is accompanied by two favored disciples also painted gold and holding gear for blessings. Placed among this distinguished lot of Buddhist power is the statue of the future Buddha (he will come again in a different form) seated in a Western position – on a chair. Multi colored wind socks hang from the ceiling, and thongka paintings attached to silk and brocade fabrics rather than frames depict Buddhism’s protective and compassionate personnel, gods, goddesses and heros. Painted on the walls are Mandalas and more familiar figures or icons of Buddhist culture, the art work itself an amazing feat. The only thing not decorated are the wooden floors, for which you must, as usual, remove you

ies high, is shrouded in gold brocade capes and is gilded gold. Buddha is accompanied by two favored disciples also painted gold and holding gear for blessings. Placed among this distinguished lot of Buddhist power is the statue of the future Buddha (he will come again in a different form) seated in a Western position – on a chair. Multi colored wind socks hang from the ceiling, and thongka paintings attached to silk and brocade fabrics rather than frames depict Buddhism’s protective and compassionate personnel, gods, goddesses and heros. Painted on the walls are Mandalas and more familiar figures or icons of Buddhist culture, the art work itself an amazing feat. The only thing not decorated are the wooden floors, for which you must, as usual, remove you r shoes to walk upon, because you are in a holy place.

r shoes to walk upon, because you are in a holy place.

On another wall are many glass boxes containing statues of saints. One who made me laugh with his wicked smile was that of Tupoc Kuenlua, the Divine Madman who sits in the Lotus position and is credited with creating the national animal, called a Takin, which has the head of a goat with it’s very twisted horns, and the body of a cow. (It does exist. I went to the preserve to see a few caged in a green environment. No one really knows how this cross happened but the takin reminded me of a wildebeast.) Tupoc was also the instigator of the phallus decor on houses. (If someone compliments the house, owners fear evil will enter, and so they paint the ugly phallus on the wall to ward off negative approaches.)

As we wandered through the huge Dzong structure, we could hear what seemed off key chanting. Later we discovered young monks, virtual children, were studying “chant.” as they read Buddhist scriptures. Their voices rang in the wind. Attached but in a separate structure (you cover a lot of steep steps as you tour these holy places) was another temple dedicated to the architect of the Dzong who had a vision in a dream of what his task would be and created it. His chapel, filled with elaborate butter sculptures, bowls of offerings (looks like a candy store), fruits , thongkas, katas, rupees and rice offerings is under the care of a very young student monk who was dusting the ornate flower carvings and towering sculpture honoring the visionary. He sweeps the floors, freshens the flowers (I thought the fake orange tree was a hoot) and tenderly refreshes water bowls, candles and other offerings to Buddha. Sadly, photographs were not allowed in any of the temples.

, thongkas, katas, rupees and rice offerings is under the care of a very young student monk who was dusting the ornate flower carvings and towering sculpture honoring the visionary. He sweeps the floors, freshens the flowers (I thought the fake orange tree was a hoot) and tenderly refreshes water bowls, candles and other offerings to Buddha. Sadly, photographs were not allowed in any of the temples.

A few years ago, an enormous glacier high in the surrounding Himalayas broke from its location and dropped into the river, causing it to rise hundreds of feet and flood the entire valley and this architectural marvel. Much was saved, the town was moved higher off the river, the dzong restored and life goes on. But distant glacier fall out could do it again. It is an environmental concern in many areas of the world.

As we had set out this morning on the narrow winding road from Thimphu, the capital, we noticed the narrow newly-paved road was packed with children and citizens dres sed in their national finery. We didn’t know what was up until a policemen told us to pull against the curb and wait. Today was the arrival of Tilku Jigmne Chhoda, the religious head or Jey Kempo of Bh

sed in their national finery. We didn’t know what was up until a policemen told us to pull against the curb and wait. Today was the arrival of Tilku Jigmne Chhoda, the religious head or Jey Kempo of Bh utan,(similar in power to the Dalai Lama who was religious head of Tibet) with two to three hundred monks following. It was the annual migration or transfer of the monk community from the winter home to the summer home in Thimphu. Punakha, the winter site, is 2000 meters lower and much hotter for the cold months for monks who have no heat in their structures. During the summer, they occupy a similar Dzong in Thimpu.

utan,(similar in power to the Dalai Lama who was religious head of Tibet) with two to three hundred monks following. It was the annual migration or transfer of the monk community from the winter home to the summer home in Thimphu. Punakha, the winter site, is 2000 meters lower and much hotter for the cold months for monks who have no heat in their structures. During the summer, they occupy a similar Dzong in Thimpu.

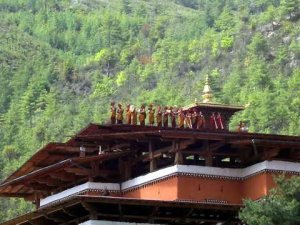

The Jey Kempo with his entourage moved slowly down the road in red Prados, which are Toyota vehicles, reaching out of the car window with his baton and touching those who wished a blessing on the head, us included. Other monks ran ahead of the car parade handing out blessed strings in the colors of prayer flags and holding out red sacks if anyone would be so kind as to give an of fering. On the roof top of a Thimpu Dzong a dozen musicians blew long thin curved horns and beat cymbals as the Jey Kempo approached. It was a surprise joy for us to be a part of this.

fering. On the roof top of a Thimpu Dzong a dozen musicians blew long thin curved horns and beat cymbals as the Jey Kempo approached. It was a surprise joy for us to be a part of this.

As we picked up the road again – we began at 9,000 feet (I don’t even feel altitude changes any longer) – rose to about 10500 feet and after the three hour slow and cautious drive, we arrived deep in the Punakha valley which is sub-tropical, hot, and at about 3000 feet above sea level. We wrangled with a number of colorful trucks with brightly painted Buddha figures over their windows (I call them Blow Horn trucks, having seen then in India and Nepal as well, because on their back is written Blow Horn, otherwise they w on’t move out of the way), lazy cows and sleeping dogs occupying the middle of roads as we rounded exciting hairpin turns, and one area cut out of the fern and pine covered mountains, was decorated with 1000 tiny stupas (Barbie sized) a family had placed in the tiny cave as a tribute to a cremated family member. These tiny stupas resembled a thousand white, yellow and blue butterflies as we passed. (My driver told me one body supplies enough ashes mixed with cement for the 1000 tiny sculptures.)

on’t move out of the way), lazy cows and sleeping dogs occupying the middle of roads as we rounded exciting hairpin turns, and one area cut out of the fern and pine covered mountains, was decorated with 1000 tiny stupas (Barbie sized) a family had placed in the tiny cave as a tribute to a cremated family member. These tiny stupas resembled a thousand white, yellow and blue butterflies as we passed. (My driver told me one body supplies enough ashes mixed with cement for the 1000 tiny sculptures.)

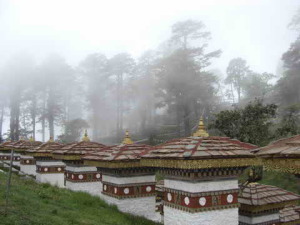

As we crossed the Duchula Pass, , we were greeted by 108 large brick stupas (holy structures that look like impenetrable blocks) which the eldest queen had built to honor the praiseworthy way her husband the fourth King had solved a problem with encroaching Indians who had mo

we crossed the Duchula Pass, , we were greeted by 108 large brick stupas (holy structures that look like impenetrable blocks) which the eldest queen had built to honor the praiseworthy way her husband the fourth King had solved a problem with encroaching Indians who had mo ved across the border and settled without permission. He went personally with a car full of oranges, handing out an orange to each foreign person, and this way he was able to take a census of how many must be repatriated back to India.. He gently nudged then back over the border and won the admiration again of his people and his five wives, apparently.

ved across the border and settled without permission. He went personally with a car full of oranges, handing out an orange to each foreign person, and this way he was able to take a census of how many must be repatriated back to India.. He gently nudged then back over the border and won the admiration again of his people and his five wives, apparently.

The policy in Bhutan is if you want to settle in Bhutan, you cannot do it as a refugee. You must complete immigration legally, learn Bhutanese, wear the national dress, pay taxes and become a part of the nation’s work force and supporter. No leeching, in other words, and no free entry. In this way, the King has been able to keep Bhutan pure and workable. Amen to him. Bhutan is paradise. Sadly we leave here and head for our final destination of Bangkok, Thailand.

Photos: The Winter Dzong; a child in school uniform who followed me into the Dzong; a detail of the high walls inside; A Thongka of the various elements of life; the young monk caretaker; The first car bearing relics and valueable images from the Winter Dzong to the Summer one; high level monks await the arrival of Jey Kempo; more monks a buzz; the roof top horn blowers; a blow horn truck with Buddha images; tiny stupas made of ashes and placed along roadside niches; the 108 stupas the Queen made to honor the fourth King for his good works.