From poverty of religion to the gold and silk jewels of maharajas, from an ambiance of Namaste bows, dahl, red and ochre robes, shaved heads, flat chapati, marigold leis and Tibetan protests, to the swift brush of international business men in steam heat, dragon fruit, and a choice of pillow stuffing so you sleep like a princess, from narrow roads curling worse than a frizzy permanent to wide, flat fingers leading to roundabouts and orderliness, from Dhamshala to New Delhi is a million miles, it seems. It’s pure culture shock, maybe a relief.

We are now well footed in India, home of Vishnu and red tikka powder, textiles and turbans of colors to identify casts, mosques and red forts, prayer wheels and taxi boats, Jaines who wear giant clown-like shoes so they won’t kill any ant or bug when they walk on the streets, natural gas in taxi tanks, mean monastery murals of ugly protectors, maharani palaces and polo fields, painted elephants, rock art architecture, holy cows, yellow mangos and Ballywood, and where houses of Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist and Christian (always painted white) faith work side by side.

taxi tanks, mean monastery murals of ugly protectors, maharani palaces and polo fields, painted elephants, rock art architecture, holy cows, yellow mangos and Ballywood, and where houses of Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist and Christian (always painted white) faith work side by side.

Our first morning back in New Delhi was enigmatic. The weather reported sunny and hot – 104 degrees for the day – but as we waited for our mourning tour in the exotic Oberoi Hotel, suddenly tornadic winds blew up with such insistence and fright that the frangipani trees blew flat while doormen in red turbans and white suits hustled people through the glass doors. From where did this come? Out of a polluted dark morning sky. All we could think of was Myramar’s cyclone, China’s earthquake, and the rushing rain squeezed under giant glass and bronze doors while the pool water rose up in a dance. Ironically, I had made the comment, jesting, of course, at least we have electricity in this hotel, one of the best in the world, according to travel jour nals. Seems that every hotel, lodge, rest house I’ve slept in these past six weeks had an electrical issue. There wasn’t energy to charge laptops, cameras, to read, or just to see by. Electricity was never a sure thing, even at the nice Yak and Yeti Hotel in Kathmandu where lights went off four or five times a day and you prayed you weren’t in the elevator. Surely, I had said with confidence, there was plenty of lectrecity here in high class New Delhi where major hotel’s stand high above flowering trees with sort of a Las Vegas vision. Well, the storm hit, the giant crystal chandeliers flickered and lo and behold, out went the lights – for a minute, until the back up system kicked in but enough to make me shiver. What is it about me and the lights? I’m just tired of darkness.

nals. Seems that every hotel, lodge, rest house I’ve slept in these past six weeks had an electrical issue. There wasn’t energy to charge laptops, cameras, to read, or just to see by. Electricity was never a sure thing, even at the nice Yak and Yeti Hotel in Kathmandu where lights went off four or five times a day and you prayed you weren’t in the elevator. Surely, I had said with confidence, there was plenty of lectrecity here in high class New Delhi where major hotel’s stand high above flowering trees with sort of a Las Vegas vision. Well, the storm hit, the giant crystal chandeliers flickered and lo and behold, out went the lights – for a minute, until the back up system kicked in but enough to make me shiver. What is it about me and the lights? I’m just tired of darkness.

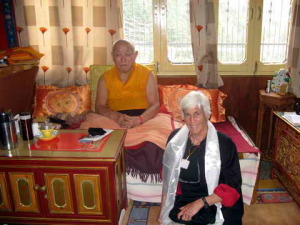

Our final day in Dharmshala gave an opportunity to meet, instead of the Dalai Lama, one of his highly respected advisor and spiritual minister of the exiled government of Tibet. He is a Rimpoche or teacher, 88 years old, who has the Dalai Lama’s ear and friendship. In 1959 they fled the Dalai Lama’s Potala (palace) in Lhasa (it looks like the setting for the old movie Shangri-la) together on horseback across the Himalayas, with CIA covertly accompanying them and US army helicopters hovering overhead for protection. Monks and holy men really have titles, but not personal names. In Tibet and Nepal, most people are named for the day of the week they are born, so repetition is a constant. But Buddhist monks and lamas toss aside th eir family ids. The Rimpoche, considered a god in Korea and Taiwan, lives on the down wind side of a small hotel patronized by white American hippie hangovers in sandals and dreadlocks butt-long. We climbed the many stairs to the balcony of his reception room overlooking another side of Dharmshala. Pelargonium and petunias were planted in pots along one side. We removed our shoes in the attitude of respect, and met a translator who would accompany us because the Rimpoche doesn’t speak English. We carried gold and white katas and a velvet bag with Episcopal prayer beads made by Suzanne Hensley of Memphis, which I had brought as a gift for the Dalai Lama.

eir family ids. The Rimpoche, considered a god in Korea and Taiwan, lives on the down wind side of a small hotel patronized by white American hippie hangovers in sandals and dreadlocks butt-long. We climbed the many stairs to the balcony of his reception room overlooking another side of Dharmshala. Pelargonium and petunias were planted in pots along one side. We removed our shoes in the attitude of respect, and met a translator who would accompany us because the Rimpoche doesn’t speak English. We carried gold and white katas and a velvet bag with Episcopal prayer beads made by Suzanne Hensley of Memphis, which I had brought as a gift for the Dalai Lama.

Our guide explained the disappointments of our trip – the closing of the Tibetan border, the cancellation of the Dalai Lama’s audiences, and asked if he could become the bearer of this gift to the Dalai Lama, which he seemed to agree upon. When the rimpoche learned of my work with juvenile delinquents, he asked us to sit a while on the floor mats – one tries not let your feet point at anyone or anything holy – and he gave a teaching to me about broken families, kids on drugs and showing love. Our worlds are similar, even that of the great Buddhist teachers in a corner of life where the Dalai Lama’s holy tongue is worshiped. Every breath the Lama takes seems to be scripted into a book.

We had an extraordinary chance to watch monks making a sand mandala in the Lama’s temple. No photographs allowed, but they build a mandala about four foot square out of grains of sand, rubbing one grain at a time to get the right formation and color. After such complicated labor, the mandala might sit for a few days, if a wind doesn’t come along and blow it away, or someone mistakenly put their hands in it. We then visited the Tibetan Museum on the Dalai Lama’s property. It is a small place reeking with the story of injustice, of abuse and slaughter by the Chinese Revolutionaries during Mao’s days, how Tibetan culture and life was ripped from them, 600 art filled monasteries were destroyed, (the Chinese used them for toilets and for animal shelter), and have continue to make every effort to wipe out the Tibetan national identity which stays alive in a flicker of light, thanks to India, Nepal, and other centers for refuge for Tibetans. I im mediately thought of our Civil Rights Museum, the struggle of our African American friends through slavery and as well the Holocaust museum inh Jerusalem which keeps lights aglo for the millions of Jews annihilated by Hitler in World War II. These tragedies shout some lesson about human nature that the non-persecuted ones need to take up to preserve and protect the innocent. And the rule of the roads in India, I learned, is “Good luck, Good Horn, and Good breaks.”

mediately thought of our Civil Rights Museum, the struggle of our African American friends through slavery and as well the Holocaust museum inh Jerusalem which keeps lights aglo for the millions of Jews annihilated by Hitler in World War II. These tragedies shout some lesson about human nature that the non-persecuted ones need to take up to preserve and protect the innocent. And the rule of the roads in India, I learned, is “Good luck, Good Horn, and Good breaks.”

We are currently back in cosmopolitan New Delhi and a Thai massage was on tap. The Thai lady crawled up my back on her knees and tore at my tired muscles as if they’d never b een stretched before. Ow, ooh, ouch- but she did it was such calm and peace about her, saying softly, Is my pressure sufficient? What could I say.

een stretched before. Ow, ooh, ouch- but she did it was such calm and peace about her, saying softly, Is my pressure sufficient? What could I say.

We spent the delayed morning in the Lotus shop, four stories of fine carpets (everyone wants to seel you carpets), jewelry (colored stones from India are high on many lists), and a floor of saris and punjabs (pajama pants with tunic tops), every kind of pashmina scarf, and embroidered jacket one could imagine. It’s a woman’s world of grace and beauty, silk and spangles, beads and gentility, where we westerners look out of place and yet…..we have to try one on, wrap ourselves in six meters of fine silk of extraordinary color combinations and softness and wish – where in the world could I wear that in Memphis? Sigh. One has to learn about the underskirt that is hidden, and pleating and tucking in the acres of fabric so it fits elegantly and won’t pull out, and then the blouse is made to your size – there’s always extra fabric spangled and beaded as well j ust for the blouse – and you decide if you want your mid-life crisis roll to show or if it should cover to the waist. The comfort zone is that women wear flat sandals, likewise highly beaded

ust for the blouse – and you decide if you want your mid-life crisis roll to show or if it should cover to the waist. The comfort zone is that women wear flat sandals, likewise highly beaded

Today we hope to visit art museums, monuments, the eternal flame at the spot where Ghandi was assassinated, and try a Balinese oil massage. Tomorrow we are back to primitive living, taking off in a small plane for Leh in Laddoch, which is considered Old Tibet and is nestled in the foothills of the Himalayas. No more guaranteed electricity or flushing toilets for a couple of days.

Photos: Dragon fruit; breakfast at the Oberoi; Rimpoche and a deacon; Oberoi flower arrangement; how’s this for a lap pool? Sue tries a sari while Jim looks at price tag.